Y Gors (The Bog)

Author: Anne Marie Carty, Nick Jones and Dafydd Sills-Jones

Format: Experimental Documentary

Duration: 17’ 45”

Published: June 2018

https://doi.org/10.37186/swrks/8.2/4

Research Statement

Criteria

Overarching Question:

In the context of the production of a digital audio-visual text (i.e. documentary film) addressing an aspect of ‘the Anthropocene’ which in this case considers the impact of farming activities and land drainage on an ancient raised peat bog, to what extent can processes of music composition enable narrative structures to explore and reflect on the connections between communities and their environments?

Sub Questions:

1. How can non-realist documentary film language be deployed without alienating either a) the community with which, and about whom, the film is made; b) the likely wider audience for the film?

2. How can musical composition techniques, when placed at the centre of the documentary film editing process, enable a balancing of these factors?

Research Questions

When approaching their film project, the project team identified problems in the usual, mainstream documentary modes of addressing questions of climate change, and the relationship between humans and their environment. From high visibility commercial projects such as The End of The Line (Murray 2009), The Cove (Psihoyos 2009), Blackfish (Cowperthwaite 2013) to national televisual factual programming and community-based and arts projects and corporate production, the magnitude and seriousness of issues around the Anthropocene (including climate change and pollution) make film production difficult. Many of these difficulties flow from what Winston terms “‘problem moment’ narrative structures” (Winston, 2008:49).

According to Winston, ‘problem moment’ narrative structures reduce the perceived complexity of socio-material events and induce a sense of teleological inevitability, thereby lessening the complexity of problems and contexts and diffusing political or social controversies. This narrative structure is also noticed in TV programmes that operate in the discursive space of humans and their environments (Dingwall & Aldridge, 2003), and may also lead to a naturalising of the notion of human supremacy, again at the expense of complexity.

This project addresses two specific issues with ‘problem moment structures’; a) the way in which they simultaneously reduce the contributor’s voice to a level of dramaturgical expedience, robbing the contributor of their own self-image and putting them at the service of an author’s intention (Minh-ha, 1993: 97); b) how ‘problem moment structures’ tend towards binary discursive (or ‘binary oppositional’) formations, in which ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are evoked and voices attached to them, often in the name of an illusory ‘balance’.

It is not surprising that such structures are employed; if such films are to persuade in line with the logics of documentary’s tendency “to persuade and promote” (Renov 1993: 21), then a wide audience of non-specialists need to be engaged and persuaded by the film’s account of a/the ‘problem’. Hence the need for (over) simplification.

How then, in the context of a discussion of the Anthropocene’s impact in an individual film project, could the difficulties of a ‘problem structure’ be avoided, whilst still engaging a wider audience?

One central hypothesis in this project was that musical structures might enable a film to perform the role of creating coherence, therefore avoiding an over reliance on ‘problem moment structures’. An example of an unhelpful application of ‘problem moment structures’ would be when a central ‘problem’ is identified and is elevated to the status of a ‘topic’ around which binary narratives are arranged, at the expense of other important and related issues.

Such a use of ‘problem moment structure’ would lead to a flattening of the polysemic potentialities of film-language, discarding a multi-layered rendering of a screen version of the world, and therefore risking the misrepresentation of its contributors’ lived experience. The use of a musical structure, rather than a ‘problem moment structure’, might aid in preserving polysemy and multi-layered-ness, without leading to a documentary treatment that alienates a wider audience.

Context

Y Gors [The Bog] was part of an overarching AHRC research project that sought to use arts practice to engage communities in a dialogue about the use, and loss, of water systems (http://www.hydrocitizenship.com/). Our film did this by working with Nick Jones’ village choir Côr y Gors, (literally ‘Choir of The Bog’) based at the edge of one of Britain’s largest raised peat bogs (Cors Fochno, West Wales), to act as proxy for the local community. This project gave us a chance to speak through and with a community about its relationship with its environment. However, by inviting the choir – and by extension the local community – to participate in a documentary film we had to deliver to them something that would still appear to be a documentary film, in the normative-realist sense of the term. Not to do so would risk the goodwill of their participation in a film that concerned the facts of their lives in their own community, and thereby be a wilful misrepresentation of the dynamics of human community and landscape in this specific instance.

An important question was the kind of audio-visual language that could deliver some of the goals of our film. We drew on a number of examples, taken from the tradition often referred to as ‘creative documentary’ (see De Jong et al, 2013; Goldson 2015; Haase 2016), as we were aiming to adopt a documentary language that could express the complex relationship between a human community and the natural environment, but not pass the point at which it could be recognised by a wider audience as such.

An immediate example to follow might have been that of Leviathan (Castaing-Taylor 2015), which showed that when pushed near its limits, the mainstream creative documentary form could produce a sensory experience for an audience, putting them in a new moral space (Stevenson & Kohn 2015). The problem with this film when considering what we hoped to achieve with Y Gors – The Bog, was that its film language, whilst attending to the nuance of physical somatic reality on a trawler in the mid-Atlantic ocean, effaced human community or agency; it deliberately ‘muddied’ dialogue and elided humans with ‘the trawler as metal monster’, ravaging the natural resources of the seas. Whilst the density, hyper-reality and impressionism of the sound track, with its extensive treatment of found sound, was certainly an influence, Leviathan’s effacement of human community was an authorial step too far for this project.

When adapting Leviathan’s extreme approach to producing a film that would be accepted by its community of contributors, we drew on other examples. Perez’s Suite Havana (2003), like Leviathan, includes no dialogue, but has a co-operative-observational quality that helped to spread the author function across the film, refusing a ready, narrow interpretation. Madsen’s environmental film, Into Eternity: A Film For the Future (2013) laced documentary realist modes, such as interviews and observations, with poetic and allusive passages, coming together in interviews with politicians grappling with the philosophical depths of the far future that challenged the sober and official nature of documentary discourse. Luostarinen’s hybridization of poetic lyricism and realist observation in Kotona Kylässä [At Home in a Village] (2012) showed that documentary form could attend to the specific details of modern human rural existence without losing contact with a wider audience.

Importantly, these three films showed that mainstream documentary film language could be adopted without betraying either local or general perspectives on events.

Methods

We worked very closely with the composer, Nick Jones. The composer spent a great deal of time not only working with the community choir to create music for the film but also on the bog itself, recording sound effects and interviews, and gaining artistic inspiration from the place. An iterative approach between the researchers and composer was employed throughout the entire film-making process. Structuring the film around the music and soundscapes afforded a freedom from the tyranny of attempting to capture or create a “real time” unfolding narrative or imposing an external narrative voice on the film.

This process led towards a means of using music as a way of not only textually creating continuity, but also using the process of film and music composition to examine the tension between authorship (i.e. the fashioning of the narrative text) and the contributors’ lived experience (i.e. as reflected in their contributions).

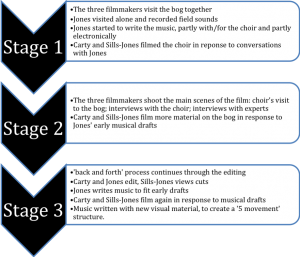

Figure 1. Research process diagram

As can be seen from the diagrams above, the ‘back and forth’ dynamics enabled the composer and film makers react to each other’s work. The result of this was a semiotic ‘suspension’, where the music refused to let any specific voice dominate the ‘choir’ of perspectives in the whole film.

The political-polemic nature of Cors Fochno’s land politics was impossible to ignore, as farmers and environmentalists both had very different industrial, cultural and linguistic connections to the bog; indeed this opposition was an important part of the spiritual texture of the landscape. The process of being led by musical composition enabled the authors to include some (locally controversial) binary-oppositional material without the film losing its ability to talk beyond the scientific-factual discourse.

One of many examples of this ‘suspension’ is to be seen in the decisions around the musical introduction of the voices of farmers. At 04:55, a farmer introduces himself as having been born & brought up on the edges of the bog, and during numerous re-drafts the montage was adjusted so that it did not act as a cue to the audience that farmers represented the destruction of a ‘natural’ landscape. This in turn, enabled the authors to place the farmer’s voice over the end of the music from the previous scene and the beginning of the next, so his views are drawn into the texture of the film and act as an introduction to the next scene. The music was composed to deliberately raise and then suspend a judgement about the voice placed within it.

Outcomes

In addition to numerous local screenings and the mentioned festivals, the film has also been shown to a number of experts in the documentary field (such as Joram Ten Brink and Jouko Aaltonen) and has been presented in various academic settings (AHRC Being Human Festival, Aberystwyth University, 2016; Mecssa Conference, Leeds University, 2017; Research Seminar, Helsinki University, 2017). Reception at these presentations fell into two camps. Some critics expressed the view that the film’s use of music did not reduce the film’s ability to discuss topics, and had created a strong emotional response even in a highly experienced, expert audience. Other critics were unconvinced about the need for such “vagueness”; other practitioners – especially those who aim for a degree of community engagement in the process – may want to consider these varied responses to this filmic approach in the context of their own aims.

It is worth noting that British academic voices had substantially more difficulties with the film’s ambiguity than European commentators. Whilst it is too early to comment on the wider significance of this difference in reception, it is evidence that the film has successfully challenged aspects of the dominant non-fiction film discourse around climate change, and the impact of the Anthropocene.

Dissemination

Y Gors [The Bog] was made by Anne Marie Carty, Nick Jones and Dafydd Sills-Jones between 2015 and 2016, funded by the AHRC ‘Hydrocitizenship’ project, and the Coleg Cenedlaethol Cymru (National College of Wales) strategic development fund.

The film was presented with an academic paper at Aberystwyth University (AHRC Being Human Festival, November 25, 2016), Leeds University (Meccsa 2017 Conference, January 12-13, 2017), University of Helsinki (Research Seminar, January 26, 2017), University of Warwick (Research Seminar, March 4, 2017).

Festival Screenings:

AHRC Being Human Festival, Aberystwyth, November 2016

Tampere International Film Festival 2017

Wales International Documentary Film Festival 2017

Other Public Screenings:

Talybont Village Hall, July 2016

Canolfan Clettwr, Taliesyn, September 2016

Dyfi Biosphere AGM, October 2016

Museum of Modern Art Wales, Machynlleth, December 2016 & May 2017

Aberystwyth Arts Centre, November 2016

The Friendship Inn, Borth, November 2016

Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT), Ceinws, December 2016

Impact

The film was almost universally understood and enjoyed by local audiences, successfully creating an emotional response as well as being informative. The iterative techniques of musical composition succeeded in balancing a lyrical portrait of place with spoken material of a binary-oppositional nature. The film language was crafted to avoid alienating or misrepresenting its contributors, and to allow the bog’s audio-visual representation to flow from the choir’s specific intersubjective position, through the recordings of their music, and through their gestural performances in the video track of the film. Choir members expressed deep emotional reactions to hearing their voices in connection with the landscape, and to taking part as a group in a work they consider to be lyrical and of some beauty.

The film alerted viewers to the importance of the bog habitat, and to the work being done to conserve it, whilst encouraging a more mutually understanding discussion around the uses of the land and a sense of deeper social cohesion around the geographical spread of the bog, transcending previous social divisions.

The outcomes for the wider audience are less clear. The film has been selected and shown by two international film festivals but had been rejected by many more. When focus group tested with international students at Warwick University in 2017, the film was clearly identified as one that dealt with climate change, and the musical content was appreciated. However, the nuances of the choir’s connection with the landscape were lost, which led the audience to be somewhat disengaged from the film. Some even spoke of the need for a clearer plot or story structure, and so other practitioners may benefit from considering ways in which the stylistic approach of Y Gors may not be sufficient in some circumstances.

The project was also seen by the funders as having especially high production value considering the very limited resources, and they use it as a flagship outcome of the AHRC Hydrocitizenship project.

The film’s soundtrack provided a polysemic space in which audience members could insert their own narrative interpretations, and yet be brought back to a more consensual interpretation by ‘informational’ passages at other points. This enabled a wide range of stakeholders in the bog’s management – farmers, environmentalists, householders, botanists, and environmental officials – to draw differing yet connected emotional responses to the film.

This music-led approach can help ‘suspend’ the tension between author and contributors, and between polemic/balance and lyricism/gestalt; it may be a useful way to address contentious issues within a film, offering greater anonymity for contributors whilst retaining stylistic coherence for the viewer. It could well be adapted by other practitioners in other filmic contexts, suggesting an original contribution to the development of filmmaking practices.

As a result of this project the filmmakers intend to develop the methodology further to address abstract concepts and ideas in feature length documentary films. Using this aural approach with multi-layered voices in combination with more ‘realistic’ modes’ such as observational filming aims to allow the viewer to identify with individual human experience, with the soundscape sections providing ellipses for reflection and sustaining audience interest in complex ideas.

Bibliography

Aldridge, M. and Dingwall, R., 2003. Teleology on television? Implicit models of evolution in

broadcast wildlife and nature programmes. European journal of communication, 18(4), pp.435-453.

De Jong, W., Knudsen, E. and Rothwell, J., 2014. Creative documentary: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Goldson, A., 2015. Journalism Plus? The resurgence of creative documentary. Pacific Journalism Review, 21(2), pp.86-98.

Haase, A., 2016. ‘The golden era’of Finnish documentary film financing and production. Studies in Documentary Film, 10(2), pp.106-129.

Minh-Ha, T.T., 1993. The totalizing quest of meaning. Theorizing documentary, pp.90-107.

Renov, M. ed., 1993. Theorizing documentary. Routledge.

Renov, M., 1993. Toward a poetics of documentary. Theorizing documentary, pp.12-36.

Stevenson, L. and Kohn, E., 2015. Leviathan: An ethnographic dream. Visual Anthropology Review, 31(1), pp.49-53.

Winston, B., 2008. Claiming the real II: Documentary: Grierson and beyond (pp. 1-336). BFI.

Filmography

Castaing-Taylor, Lucien & Paravel, Verena. 2015. Leviathan. Arrête ton Cinéma, Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, Le Bureau.

Cowperthwaite, Gabriela. 2013. Blackfish. Manny O Productions.

Luostarinen, Kiti. 2013. Kotona Kylässä /At Home in a Village. Kiti Luostarinen Production Ky.

Madsen, Michael. 2013. Into Eternity: A Film For The Future. Magic Hour Films.

Perez, Fernando. 2003. Suite Havana. Trigon Film.

Murray, Rupert. 2009. The End of The Line. Arcane Pictures, Calm Productions, Dartmouth Films, The Fish Film.

Psihoyos, Louie. 2009. The Cove. Diamond Docs, Fish Films, Oceanic Preservation Society, Participant Media, Quickfire Films.

Peer Reviews

All reviews refer to original research statements which have been edited in response to what follows:

Review 1: Accept work and statement for publication with no alternations.

The statement clarifies the author’s intentions well on the whole with appropriate references. Some minor suggestions follow:

The research question: ‘How can the voice of the author and the voice of the contributor be reconciled?’ is maybe too broad and I’m not quite sure how the film really can resolve this issue.

The final paragraph in the Research Questions section needs re-writing. The first sentence is a fragment that could be rephrased. The author should give an example of how the “musical structures might enable a film to perform the role of creating coherence, therefore avoiding an over reliance on ‘problem moment structures’”. The final sentence in this paragraph is tautological and could be revised.

Finally, Webster defines ‘Anthropocene’ as ‘the period of time during which human activities have had an environmental impact on the Earth regarded as constituting a distinct geological age’ – the author need to clarify the use of this term in the statement (especially in the first use).

Review 2: Invite resubmission with re-edit of work and/or statement

The work Y Gors is an experimental work that makes a connection between landscape of a peat bog and the importance of this environment for the local community. The innovative aspect of this film is its complex and impressive soundscape. Choir music, poetry, and voice-overs are ways to include a number of narratives, which come to establish a collective human history of this place that eludes to a past that extends further back than human existence. The editing of stunning wide-angle landscape images, and close-ups of the local flora add to the idea of awe and respect of this environment. Arguably, this film resonates well with local audiences because the images and sounds provide a link to shared memories and experiences.

The accompanying research statement should be reworked, clarified and considerably shortened to adhere to the word limit.

Research Questions: The filmmakers should not be too worried about what they not want to be but introduce their film as in light of they wanted to achieve. Present your research question as central part of the piece and simplify. Define your terms: What are problem moment structures? Be specific in applying your terminology (what is ‘good and bad’ or ‘naturalising human supremacy’) It is not clear if you want to use realist techniques or not. The last paragraph is contradictory in this sense.

Context: When comparing your film with other models, concentrate on the aspects that informed you. Into which genre do you see your film? Discuss this idea as central to this section. Simplify your sentences. How does the work fit into your research trajectory?

Methods: This section is well written and very informative. Use this model for the other sections. (Note: in previous sections, you applied “we”, this one starts with Anne Marie and … Be coherent.)

Outcomes: You have not answered the question, what other practitioners might learn from this work. What is the novelty of your work? Do not present here, what belongs into the section “dissemination” or “impact”.

Impact: move audience reactions that you list in “outcomes”, to this section

All reviews refer to original research statements which have been edited in response.