Hidden Treasures & Hidden Films

Hidden Treasures

Format: Short Film

Duration: 11 mins

Hidden Films (password: Rogelio)

Format: Documentary

Duration: 77 mins

Author: Claudia Sandberg and Alejandro Areal Vélez

Published: July 2018

https://doi.org/10.37186/swrks/8.1/5

Research Statement

Criteria

The films Hidden Treasures and Hidden Films highlight the importance of film archives, not just as a form of political diplomacy but as a carrier of memory for quite disperse groups.

The works assess the role of filmmaking as a seismograph for larger geopolitical events and global transformations.

Research Questions

The short film Hidden Treasures/Películas Escondidas (2013) and the feature-length documentary Hidden Films. A Journey From Exile to Memory/Películas Escondidas. Un viaje entre el exilio y la memoria (2016) explore Chilean films made by the East German state-owned production company DEFA in the 1970s and 1980s as transnational memories of the Cold War. With these works, film scholar Claudia Sandberg and director Alejandro Areal Vélez highlight the importance of the East German film archives, not just as a form of political diplomacy but as a carrier of memory for quite disperse groups. Hidden Treasures and Hidden Films assess the role of filmmaking as a seismograph for larger geopolitical events and global transformations.

Context

Silke Arnold-de Simine and Susannah Radstone note that former East Germany is remembered, reconstructed and represented mostly in simplified ways and utilising binary opposites, as “consumer culture versus state oppression; Ostalgie versus political debate; … perpetrator versus victim” (2012, 28). Seen as closely linked to East Germany’s repressive political framework, East German film was often dismissed as ideological remnant of the Cold War. Scholars are beginning to move away from such limited perspectives. A number of recent publications rediscover DEFA film as a seismograph for changing needs and desires in East German society, and reflection of socialist life as a philosophy, utopia and everyday experience (see Wagner 2014; Creech 2016). A particularly useful and productive direction of research has been the charting of DEFA’s legacy beyond German national borders (Allan and Heiduschke, 2016; Silberman and Wage 2014; Wedel et al. 2013).

In line with this transnational trajectory of East German Film, Sandberg’s research concerns the so-called “DEFA Chile films,” which were made in collaboration with Chilean émigré artists during the 1970s and 1980s. Evidence of an important yet neglected chapter of German-Chilean film history, this film archive is the result of the immense creative activity of Chilean artists who resided in Europe during the years of the Pinochet regime and bears witness to experiences of exile in this particular set of political, social and cultural conditions (Mouesca and Orellana 2010, Villaroel and Mardones 2011). The films are captivating because they represent rare images of East Germany as an environment that was formative for politicians, intellectuals and artists, who are now at the centre of Chilean cultural and political life (see case study in Montes 2015). Made for an East German public, these films were largely unknown in Chile until just recently. In 2013, commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the military coup d’état, DEFA Chile films became curated into the film cycle “DEFA looks to Chile” that took place at the Cineteca Nacional in Santiago de Chile. This event helped recognizing that East German film archives offer valuable foreign commentary on the Pinochet regime and are indispensable historical source material (Campos Pérez 2015, Sandberg 2016, Palacios and Donoso Pinto 2017, Cavallo forthcoming). Housed in the Museum for Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, the film materials feed into the museum’s temporary exhibitions and film events and they feature in retrospectives at Chilean film festivals.

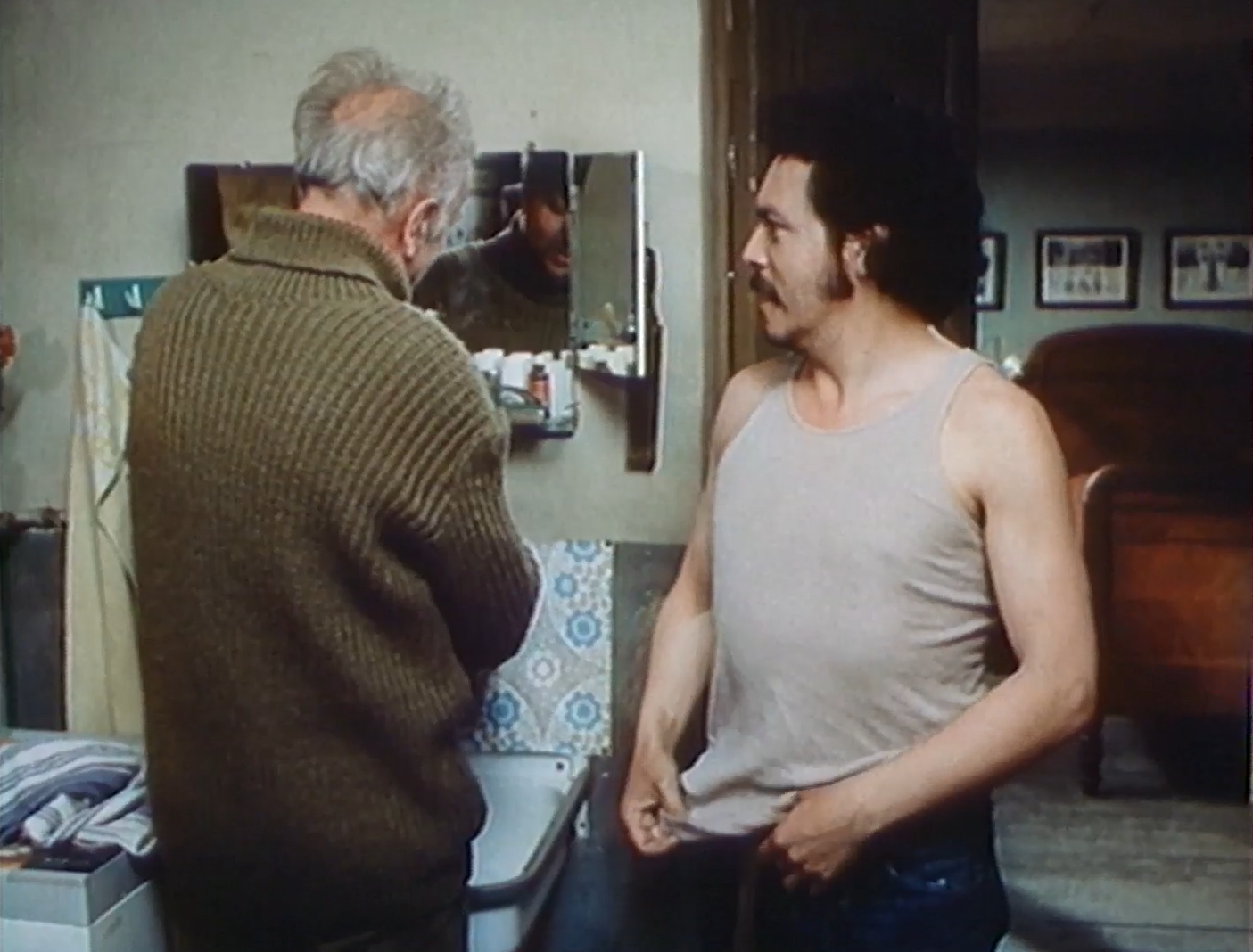

Image 1. Screenshot from the DEFA feature film Blonder Tango/Blond Tango (1985).

In 2013, Sandberg was invited to give a workshop on East German film at the private University Adolfo Ibañez in Santiago de Chile with approximately 150 Chilean undergraduate students who were training to become journalists. This rather privileged group of young viewers, who studied at one of the most expensive Chilean universities, saw themselves confronted not only with ideologically antagonistic material, but also with audio-visual ‘dinosaurs’, films that had the texture and feel of an epoch long passed. Born after the regime had ended and brought up in a neoliberal political, economic and social environment, this encounter of text and viewers – across cultural, ideological, and temporal borders – unsurprisingly called for adverse reactions. The short Hidden Treasures, an impressionistic piece, and Sandberg’s first venture into filmmaking, is the result of an ad hoc decision to record the emotionally charged discussions, reflecting views and memories students held about Pinochet’s historical legacy (see also Sandberg 2017).

The feature-film length documentary, Hidden Treasures, was motivated by what Sandberg found a disturbing but eye-opening experience and a desire to travel back and present the DEFA film archives to diverse groups and communities. Product of a four-year long project and travels to Mexico, Chile, Argentina and Germany, the film documents the reception of DEFA Chilean films and includes interviews with young people, former émigrés, cast and crews, film critics, and cultural institutions. Hidden Treasures suggests that the East German film archives reactivate not only deep-seated memories of dislocation, violence and trauma, but also revives the immense solidarity between artists in Europe and Latin America. At the same time, the films are linked to current human rights violations occurring in and beyond Latin America.

Image 2. Chilean actress Teresa Polle starred in the DEFA children film Isabel auf der Treppe /Isabel on the Stairs (1984).

Image 3. The short documentary Copihuito (1977) contains footage of Alvaro Camú and Sergio Villegas Cabriolet as children.

Methods

The making of Hidden Treasures and Hidden Films was approached as a collaborative venture. The Argentine filmmaker, Alejandro Areal Vélez, co-directed, photographed and edited the films. In a career that spans over thirty years, Areal Vélez has made video installations and experimental films for Argentine cultural and historical institutions. The highly acclaimed documentary El exilio de San Martín. Una historia de ausencia (‘The exile of San Martín. A history of absence’, 2006) is just one of the many fiction and documentaries that he made for Argentine television. The political subject and the collaboration with an academic was a first-time experience for Areal Vélez, yet he has frequently worked with film archives. La mirada necesaria (‘The necessary view’, 2010), an installation for the Buenos Aires-based museum Casa Bicentenario could be seen as precursor for the current projects. For this work, which explores the role of women in Argentine film history, the filmmaker had creatively combined classic film footage, photographs and audio archives.

In trying to find the right approach to the Hidden Films documentary, Areal Vélez was guided by the audio-visual language of the DEFA film material. Initially drawn to an observational documentary mode, the feel for the right way of telling this story arrived in the filming stage. Areal Vélez decided to begin the documentary by introducing Sandberg’s personal motivation to work on this research project, have her present and narrate the film in her capacity as a film historian, and structure the investigations as a journey.

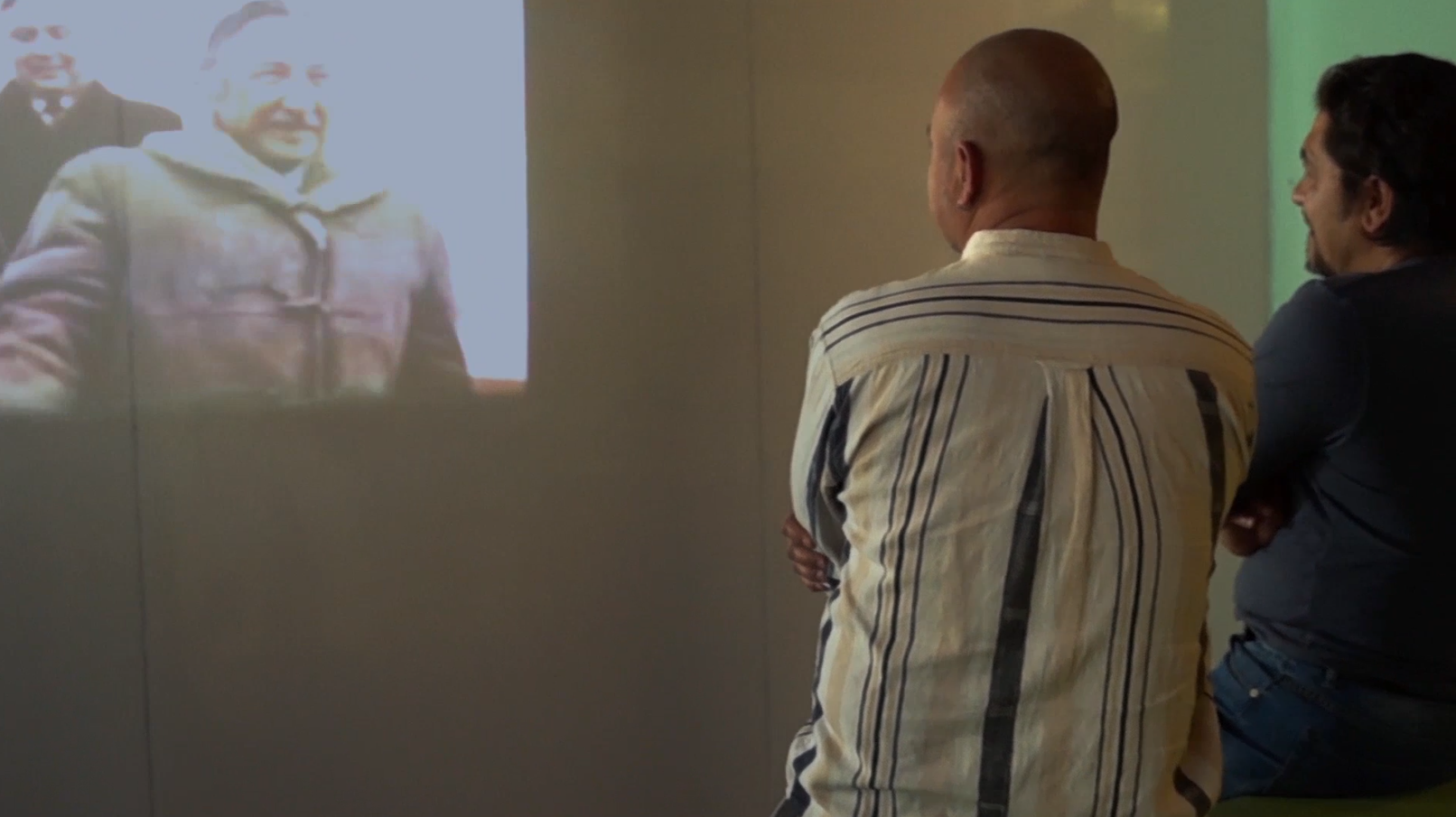

Image 4. Sandberg’s investigations

Apart from ideas and aspects brought in during the investigation, additional subtopics and images appeared during the filming stages. While working with the interviewees and different spectator groups unexpected “events” appeared in front of the camera, “lucky accidents”, to use the term coined by French theorist and filmmaker Jean Louis Comolli.

The film’s narrative rhythm became established in the editing and post-production phases. The associative editing of urban and rural landscapes, files, texts and sounds translated an idea of an unresolvedness past, evoking the manifestation of past experiences in present-day spatialities.

Outcomes*

Hidden Films relies on a wide range of audio-visual resources which convey the complexity and sensibility of this subject matter.

While well-planned and wide-reaching investigations were key to making this documentary, the planning left room for unexpected moments, the aforementioned “lucky accidents”, that occurred in the filming process. Valuable research results in their own right, they even provided for narrative turning points.

The collaboration between a film historian and filmmaker proved to be fruitful in attending to the transcultural and transnational nature of the project and in striking a balance between academic rigour and creative research practice. This partnership brought into dialogue different cultural formations to dynamically stage the various conflicts and tensions that the film alludes to.

*While this section summarises outcomes of both works, it refers in particular to outcomes related to making the longer documentary, Hidden Films.

Dissemination

Hidden Treasures and Hidden Films were made with financial assistance from the Berlin-based DEFA foundation, an institution that promotes the dissemination of East German film and stimulates research projects on DEFA. The German film institute Hamburgisches Centrum für Filmforschung CineGraph and the Argentine state-owned production company INCAA (Instituto Nacional de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales) supported Hidden Films with postproduction funds.

The short Hidden Treasures was invited to screen at the German Studies Annual Conference in Denver and at the symposium “Chile on Film” that took place at Cambridge University, both in 2013. The film screened as part of a film seminar called “Chile en el cine de Alemania Oriental” alongside the DEFA TV film Die Spur des Vermissten (‘Trace of the disappeared’, Joachim Kunert, 1980) to students of the UDLAP and BUAP universities in Puebla, Mexico in 2014. In 2015, the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires featured the short alongside the DEFA feature film Blonder Tango/Blond Tango (Lothar Warneke, 1985). The film participated in two film festivals: The Mar del Plata based MARFICI Festival Internacional de Cine Independiente, in 2014 and the FICIP – Argentina Festival Internacional de Cine Político that took place in Buenos Aires in 2015.

Since its release in November 2016 the documentary Hidden Films has participated in the competition of five international film festivals: Mar del Plata International Film Festival, Argentina, November 2016; Cinefest, Germany, November 2016; CEME Doc Documentary Cinema of Migrations and Exile, Mexico November 2017; Voces Contra el Silencio, Mexico, April 2018; Festival de Cine de Autor, Spain, May 2018; Doc Buenos Aires, May 2018. The film screened in independent cinemas in Berlin, Hamburg, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Lima, Atlanta, Tucson, and Mexico-City. Hidden Films screened as part of SUAC, a conference on memory and film archives at the Museo of Contemporary Art in Mexico City in 2017. The documentary was also selected from 3,200 submissions as one of 14 feature films to be programmed at the LASA film festival that run alongside the Latin American Association Annual Studies conference in Lima, in 2017. The same year, it run as flagship of a DEFA film series at the German Studies Association Annual Conference in Atlanta, an event that was organised in conjunction with the University of Melbourne and the Amherst-based DEFA library.

Impact

The overwhelming reception to Hidden Treasures and especially Hidden Films is evidence that these works resonate with various groups and different audiences. The films prove to be of specific interest to initiatives and film series around the subjects of exile, emigration and human rights violations in Latin America.

References

Bibliography

Allan, Seán and Sebastian Heiduschke, eds. 2016. Re-Imagining DEFA. East German Cinema in its National and International Contexts. New York and London: Berghahn Books.

Arnold-de Simine, Silke and Susannah Radstone. 2012. “The GDR and the Memory Debate.” In: Remembering and Rethinking the GDR. Multiple Perspectives and Plural Authenticities, edited by Anna Saunders and Debbie Pinfold, 19-33. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Campos Pérez, Marcy. 2015. “Construcciones visuales y memorias de la dictadura de Pinochet a través de películas y reportajes extranjeros (1973-2013).” Amnis: Revue de civilisation contemporaine Europes/Amériques, 14. http://amnis.revues.org/2645

Cavallo, Ascanio and Antonio Martínez. Forthcoming. Chile en el cine. La imagen país en las películas del mundo. Vol. 2. Santiago: uqbar editores.

Creech, Jennifer. 2016. Mothers, Comrades, and Outcasts in East German Women’s Film. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Montes, Rocio. 2015. “Fragmentos de la vida de Bachelet en la RDA. Un casamiento olvidado.” Caras, 30 July, 2015. http://www.caras.cl/sociedad/fragmentos-de-la-vida-de-bachelet-en-la-rda-un-casamiento-olvidado/.

Mouesca, Jacqueline and Carlos Orellana. 2010. Breve historia del cine chileno. Santiago: LOM Ediciones.

Palacios, José Miguel and Catalina Donoso Pinto. 2017. “Infancia y exilio en el cine chileno.” Iberoamericana XVII, no. 65, 45-66.

Sandberg, Claudia. 2017. “‘Not Like the Stories I am Used to’: East German Film as Cinematic Memory in Contemporary Chile.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 26, no. 4: 553-569.

Sandberg, Claudia. 2016. “Das Theater des Lebens. Blonder Tango (1986) und das chilenische Filmexil in der DDR”, Filmblatt 21 no. 60, 40-52.

Silberman, Marc and Henning Wrage, eds. 2014. DEFA at the Crossroads of East German and International Film Culture. A Companion. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Villaroel, Mónica and Isabel Mardones. 2012. Señales contra el olvido. Cine chileno recobrado. Santiago: Cuarto Propio.

Wagner, Brigitte B. ed. 2014. DEFA after East Germany. Rochester: Camden House.

Wedel, Michael, Barton Byg, Andy Räder, Sky Arndt-Briggs, and Evan Torner, eds. 2013. DEFA international. Grenzüberschreitende Filmbeziehungen vor und nach dem Mauerbau. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Film Reviews

Novak, Peter. 2017. “Die Chile-Solidarität wurde nicht verordnet.” Der Freitag, August 3. https://www.freitag.de/autoren/peter-nowak/die-chile-solidaritaet-wurde-nicht-verordnet.

Portela, Alejandra. 2016. “#MDQFEST 2016: Peliculas Escondidas.” Leedor, November 23. http://leedor.com/2016/11/23/mdqfest-2016-peliculas-escondidas.

Interviews

2017. Alejandro Areal Vélez and Claudia Sandberg for the Argentine Association of Directors. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-W-Dn1aaE0

2017. “Die DEFA Chile Filme haben in Chile ein zweites Leben erhalten.” Claudia Sandberg for the Goethe Institute Santiago. https://www.goethe.de/ins/cl/de/kul/sup/fil/20843903.html

2016. “Una practica de la memoria. ” Alejandro Areal Vélez and Claudia Sandberg talk with film critic Rodolfo Weisskirch in Mar del Plata Film Festival 2016. http://www.mardelplatafilmfest.com/es/edicion/31/peliculas-escondidas-una-practica-de-la-memoria

Peer Reviews

All reviews refer to original research statements which have been edited in response to what follows:

Review 1: Invite resubmission with re-edit of work and/or statement

Hidden Treasures/Películas escondidas (2013) contributes to the visibility and re-evaluation of the so-called “DEFA-Chile films.” Despite some circulation within Chile in recent years, these films made by the East German state production company DEFA in collaboration with Chilean refugees remain largely overlooked both by local scholars and audiences alike. The most significant contribution of this documentary is, therefore, the visibility it grants to the DEFA film archive by featuring a number of neglected films such as Blonder Tango (Lothar Warneke, 1986), Hitler Pinochet (Jörg Hermann and Juan Forch, 1975), and Isabel auf der Treppe (Hannelore Unterberg, 1984) via the incorporation of large sequences as archival footage. However, the overall approach is deeply problematic.

In her statement, co-director Claudia Sandberg writes that the debates about the past in former East Germany “still happen mostly in binary opposites and in simplified understandings,” thus aligning her film with the work of German scholarship trying to move away from such limited perspectives. Unfortunately, Hidden Treasures reproduces a similar simplistic approach to the deeply complex cultural memory debates in post-dictatorial Chile. Indeed, the documentary opens with the question: “Have the marks of Pinochet’s dictatorship disappeared from the collective memory?” Such a question was recurrent throughout the 1990s but since then the critical discourse has moved beyond the opposition between memory and forgetting. As argued by Steve Stern in his trilogy The Memory Box of Pinochet’s Chile, struggles over the past are better understood in the form of a battle of “memory against memory”.

Sandberg’s film is strategically structured so as to reach an affirmative answer to this opening question by showing these materials to an audience simply described as “Chilean students.” Herein lies perhaps the deepest weakness of this work. These young Chileans, Sandberg’s voiceover tells us, are “students from a local university.” Little information is provided about the University Adolfo Ibañez, a private institution where students speak fluent English and seem rather “surprised and provoked” by the DEFA films. Forty years after the coup, one of them even claims that “we read in books that the people who were abroad in Germany, because of the Pinochet incident” were “usually pretty happy to be there…. [But the character of the film] seemed very miserable.” The student’s inability to say the words “coup,” “exile,” or “dictatorship” is quite suggestive. What the documentary withdraws from the viewers is that this private University is renowned for its historic connections to the Chilean political right, with professors who are staunched Pinochet’s supporters. The “sample” of students emerges therefore as one that is opportunistic and biased, for the responses could have been very different had Sandberg chosen a different audience. The directors should explicitly acknowledge this shortcoming and provide the necessary contextual information to the intended spectator to be able to understand the reactions of this limited circle of students from the Chilean conservative upper class.

And who is the intended viewer in this case? The documentary seems more attuned to a German audience, but it does not acknowledge the imbalances of power behind perpetuating the image of an “amnesiac” Chile in a work led by a German co-director for German viewers, or even a wider international audience. This rather unreflective position of enunciation further complicates the political dimensions of the work, as can be seen from the uncritical re-appropriation of cinematic codes extensively used by Chilean exile directors, such as the act of return, the use of the first-person narrator, the shock of encountering the wealthy neighborhoods of Santiago, as well as of the Andes mountains seen from an airplane, including the usage of folk songs associated with the revolution and resistance. The title leads to further confusion. Sure, these films can certainly be seen as precious materials, real gems; but who has been hiding these treasures? Have these films been actively kept out of sight by someone; or have they been just largely neglected, like hundreds of films related to the turbulent Chilean recent history? And what role has access to foreign archives played in this lack of attention? These are timely and important questions that could be tackled at least by the accompanying statement.

Review 2: Accept work and statement for publication with no alterations

The project touches on a fascinating subject in the DEFA-Chilean films (one which I was not aware of) and aims to go beyond just relating this interesting filmic and political-historical body of work in its engagement with those involved in the production, and by following Guzman’s lead in gauging today’s Chilean student’s reaction to the films.

These are clearly all three of these are worthwhile strands of research, however to bring these all together in an 11min film is very challenging. While the research statement provides valuable context, and acts as a clear, well written, guide for the aims and intentions of the project, attempting to weave these together into one film provides moments where the project seems to become unstuck. While the work clearly accommodates the theme of how the DEFA film material is met by a young Chilean spectatorship, and thus opens ideological, cultural and temporal conflicts this raises, the brevity of this aspect of the film, of around 4mins at the end of the film, limits its impact. As the filmmakers acknowledge, this approach has its roots in a number of similar films, including within a Chilean context, so originality in approach is not the goal. However, the voices of the students are limited to three, including one of which is read via an email, and while they provide a brief interesting insight, the limited nature of the footage (I assume there was further conversations with the group of students) struggles to create a strong indication of the frontiers with the young Chilean students and the film material that the project aspired to investigate.

The middle of the film, which engages with an actress and producer of the DEFA-Chilean films, was potentially very interesting, as the opening third of the film had provided a film essay style introduction to this material that also helped to lead us into this. But the limited production quality of the material became problematic. While the two film professionals are interesting when positioned against their work, the limited nature of the discussion with them included in the film, and production quality raised a question of the original intention of this part of the project, i.e. was this material actually meant to be part of a film in the first place? or were these filmed as merely archive of interviews conducted as part of a wider traditional research project? The stories of those working in these films is a very interesting subject however, and is something that seems to provide an opportunity for much wider research.

The filmmakers have also taken the step to use the co-director’s role as film historian travelling to Chile to undertake the project as a partial narrative structuring device. However, as acknowledged in the text, this was clearly a decision taken late in the production, and its function in the film, especially within the presentation of the DEFA film material, seemed to result in the effect of a film lecture, rather than the personal story of the German film historian traveling to Chile that perhaps may have offered the narrative link the filmmakers were looking for. This lack of more personal details of who the voice is that is that is leading us also doesn’t help this and resulted in a lack of emotional engagement with the voice over, and often raising more questions on why we they were telling us what was being presented. The production quality of the sound also did not help this. Voice over in documentary film is notoriously difficult, and while I understand the decision to attempt to take this approach to help bind the various elements of the film together, I would have recommended to relook at the script if this was still possible (which clearly, as the film was released a number of years back, it isn’t).

Finally, I return to my opening comments, that the subject the project engages with is very interesting, and the historical, production, and young Chilean spectatorship themes all were fascinating aspects in their own right. However, combining them together into a short documentary film is a big challenge, and one that at times created questions in the viewer as to the value of some aspects the filmic approach the authors chose. The written statement was strong, and as the film clearly is not able to be changed, I am happy to recommend the work for publication.

All reviews refer to original research statements which have been edited in response.