Volume 7.3: Radical Filmmaking

ISSN 2514-3123

https://doi.org/10.37186/swrks/7.3

Special Issue: Radical Filmmaking

Editorial

We are delighted to publish this volume of Screenworks, a special issue dedicated to exploring various forms of radical filmmaking. This issue was produced in association with the Radical Film Network, an international network of organisations involved in politically-committed and aesthetically innovative film culture, with support of the Digital Cultures Research Centre at UWE Bristol.

Indeed, each of the seven works featured in this issue are underpinned by their political commitment – be it to issues of migration and national identity, media power, sex and gender, inclusivity, war and peace – and there is scarce reference to those debates about realism and reflexivity that, until relatively recently, loomed so large in discussions of film and politics. Nevertheless, each work also explicitly engages with questions of film form, representational power, and the politics of aesthetics. Indeed, the range of political issues addressed in this issue is more than matched by the diversity of aesthetic strategies adopted. These films drawn on traditions of materialist filmmaking, ethnography, Scratch and bricolage, participatory documentary and artists’ film and video, and even pose new categories of their own, such as ‘representational activism’.

Many of the contributions address issues of participation and the ability of cinema to shape social relations. Others focus on and deconstruct media representation or questions of historiography. Whatever the thematic or aesthetic mode, this volume is testament to the vibrancy and diversity of critical, screen-based practice-as-research today. Long may it continue.

Paola Bilbrough’s film, This is Me: Agot Dell, one of a series of commissioned works exploring the contemporary Sudanese-Australian identity, integrates its explicitly political intention to challenge racist representations of refugee/migrant backgrounds with an elliptical and poetic aesthetic sensibility. The result is a visually rich piece of what Bilbrough calls ‘representational activism’ that is grounded, as the statement makes clear, in participatory filmmaking and traditions of critical ethnography, what Anne Harris (2012) has referred to as ‘ethnocinema’. Bilbrough is cogent of her own artistic and authorial intention and well as her responsibilities as ‘framer’, and yet has sought a methodology and aesthetic style that invites the viewer to bring their own interpretations to the material. This is a rare film that combines clarity of communication within an experimental, poetic frame, underpinned by rigorous scholarly understanding and reflection.

Kelly Zarins’ work Second Home: Our Here (of behalf of Leeds International Women’s Filmmaking Collective, of which she is a founder member) is another instance of contemporary participatory filmmaking in practice, this time focusing on the collective experience of hate crime in the wake of Brexit. But the work also speaks to a broader research endeavour to ‘question if and how collectives can form via the processes of connecting, learning and making to-gether’. Grounded in an interdisciplinary practice that combines film and documentary-making with zine production, the piece explores the extent to which making can transform ‘micro networks of solidarity’ into longer-term relationships. While the filmmakers readily acknowledge their status as ‘newcomers’ to participatory documentary production, the statement demonstrates considerable awareness of the intellectual and filmmaking traditions – with particular debts to Amber’s community work and that of Leeds Animation workshop, two outstanding UK collectives from the 1960s that remain active today – in which their experimentation is situated.

Nick Cope’s contribution, Revisiting Scratch Video, also returns to a specific era of radical film practice. Cope reviews and re-contextualises three of his own foundational Scratch videos produced in the mid-1980s and shown in the first exhibition of Scratch video at the ICA in 1985, unpicking the multiple ways in which this outspoken, politicised form of filmmaking remains relevant today. A mode of practice that is overtly related to the technologies that gave rise to it – VHS domestic video recorders – Scratch anticipated digital media and the assortment of issues – legal, aesthetic, authorial – that surround contemporary media piracy and user-generated content today. Politically, Cope’s films also cannot help but evoke in the viewer contemporary anxieties. Despite being more than thirty years old, the film’s jarring edits and disturbing imagery resonate with urgent concerns today, from environmental devastation to war. Yet such historical work also, as Cope shows, invites consideration of the process of film historiography, and the ways in which assessment of political art changes and is often only understood at a distance, when it is all the more difficult to recover and map work which was always already marginal, ephemeral and based on emerging and quickly obsolete formats.

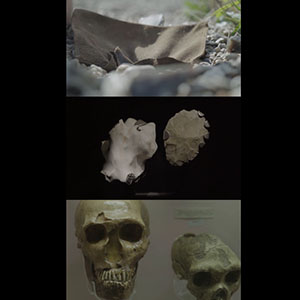

Alex Ressel and Kerri Meehan’s work, Chimera, is an innovative, complex and visually-arresting critique of museum practices and the confluence of history, culture and power that can so-often underpin museum curation. The work focuses on three narratives: the first platypus to be included in a Western science, an animal so unusual that zoologist George Shaw doubted his perception of it; the British museum’s merman exhibit, a hoax object designed to fool European collectors in the 18th century; and experimental archaeologist and forger of antiquities, Flint Jack (1815-74). The film is a thoughtful reflection on curatorial practice, strikingly composed across three channels. As Ressel and Meehan articulate in their accompanying statement, the form of the piece is itself chimeric, each channel adopting a different perspective on the narrative, resisting any straightforward categorisation. The piece thus becomes a radical attempt to disrupt the ordering impulse of museum curation, and resonates with more contemporary efforts of artists and curators to invert and reflect upon the power dynamics inherent in history-making.

Kayla Parker’s On Location poses questions of radicalism both in terms of audio visual aesthetics and of filmmaking methodology in addition to more overtly political issues of environmental degradation, human and non-human relations and marginalised femininities. Acknowledging that her method of filmmaking is ‘predicated on there being no conscious aim either before or during the making process’, Parker reverse engineers an experimental approach to landscape filmmaking that synthesises phenomenology, écriture feminine, structural materialism and critical geography. The result is a beautiful depiction of the countryside hollow way visited by the British avant-garde filmmaker and performance artist, Annabel Nicolson, forty years previously; one that challenges conventional methods even within the ‘new materialist’ approach to landscape filmmaking.

David Archibald’s contribution Glasgow: RFN 16 also approaches the concept of radicalism from several perspectives: formally and aesthetically as well as in terms of the production processes underpinning the work. In attempting to document an event that was itself both about radical film culture – the Radical Film Network unconference and festival 2016 – and organised in a radical way, the challenge he and the other filmmakers set themselves was to find a mode of production and a film style that would cohere with the values of what they were trying to document. Though the filmmakers make no claims to the radicalism of the participatory method adopted – crowd-sourcing the material from a range of participants involved is not a new approach – their treatment of this material surely is. Removing the audio track from the discussions at the conference, for example, prevents the images being determined by the content of the speakers’ words, and instead evokes a sense of the atmosphere of the event. Similarly, the juxtaposition of multiple screenings and events creates an impression of the diversity of approaches to both exhibition and radical politics of offer within the festival. The result is a fascinating hybrid that combines audio-visual criticism, film festival documentation and short-filmmaking.

Guli Silberstein’s The Schizophrenic State Project comprises several short works, each of which explores and reworks devastating imagines of war, terror and violence with found footage from popular culture. The result is a dizzying meditation on the consequences of media saturation for both the viewer and those represented. The distressing footage of the Palestinian man attempting to shield his son from gunfire in the eponymous piece, ‘Schizophrenic State’, for example, is juxtaposed with footage from sporting events, parties and action adventure series. Such a disorientating assemblage of material prevents any attempt to derive conventional narrative meaning from the work. Instead, the piece provokes the audience to reflect on the experience of existing amidst the contemporary flow of mass media images, and the difficulty of truly comprehending that which is represented. In many ways a contemporary counterpart to Cope’s work – Guli cites Scratch artists among his influences, along with Guy Debord and strategies of Détournement – this series of films demonstrates that this style of work is as alive and pertinent today as ever, and testifies to Cope’s argument that scratch was indeed the precursor to remix art today.

Contents

Author: Paola Bilbrough

Format: Experimental documentary

Duration: 03’12”

Published: October 2017

An experimental participatory documentary portrait of contemporary Sudanese-Australian identity which adopts poetic aesthetic strategies to challenge mainstream representations of migrant/refugee backgrounds.

Read more…

Author: Kelly Zarins

Format: Documentary

Duration: 6’10”

Published: October 2017

Leeds International Women’s Filmmaking Collective adopts a collective approach to documentary- and zine-production, and explores the role of collaborative production in building group solidarity.

Read more…

Author: Nick Cope

Format: Video Art

Duration: Various

Published: September 2017

A revisionst approach to the outspoken and often overtly political Scratch video movement, which prefigured many of the aesthetic approaches and ethical issues interrogated by remix artists today.

Read more…

Author: Alex Ressel and Kerri Meehan

Format: Three-channel video

Duration: 13’42”

Published: October 2017

An innovative, complex and visually-arresting critique of museum practices and the confluence of history, culture and power that can so-often underpin museum curation.

Read more…

Author: Kayla Parker

Format: Experimental Film

Duration: 12’17”

Published: September 2017

An experimental approach to landscape filmmaking inspired by British avant-garde artist, Annabel Nicolson, which draws on phenomenology, écriture feminine and structural materialist filmmaking.

Read more…

Author: David Archibald

Format: Video essay documenting unconference and film festival

Duration: 21’30”

Published: October 2017

Part audio-visual criticism, part film festival documentation and part short-film, this experimental crowd-sourced documentary represents the 2016 Radical Film Network Festival and Unconference.

Read more…

Author: Guli Silberstein

Format: Experimental Artist’s Video

Duration: Various

Published: October 2017

A meditation on the representation of war and violence in the media and the consequences of blurred boundaries between news, entertainment and terror.

Read more…

This volume is supported by the Digital Cultures Research Centre at the University of the West of England, Bristol

This special issue on Radical Filmmaking has been edited by Dr Steve Presence (UWE Bristol) with support from the Editorial team.